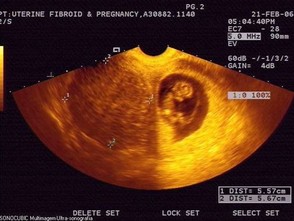

A small number of pregnant women have uterine fibroids. If you are pregnant and have fibroids, they likely will not cause problems for you or your baby.

During pregnancy, fibroids may increase in size. Most of this growth occurs from blood flowing to the uterus. Combined with the extra demands placed on the body by pregnancy, the growth of fibroids may cause discomfort, feelings of pressure, or pain. Fibroids can increase the risk of:

- miscarriage (in which the pregnancy ends before 20 weeks)

- preterm birth

- breech birth (in which the baby is born in a position other than head down)

Fibroids do not always grow in pregnancy. In most studies, the majority of fibroids remained the same size. Spontaneous shrinking was found in nearly 80% of women within 6 months of pregnancy. Postpregnancy, remodeling of the uterus may affect fibroids, creating a natural therapy during the reproductive years. This may explain the protective effect of parity or number of pregnancies on fibroid risk.

Rarely, a large fibroid can block the opening of the uterus or keep the baby from passing into the birth canal. In this case, the baby is delivered by cesarean birth. In most cases, even a large fibroid will move out of the fetus’s way as the uterus expands during pregnancy. Women with large fibroids may have more blood loss after delivery.

Often, fibroids do not need to be treated during pregnancy. If you are having symptoms such as pain or discomfort, your doctor may prescribe rest. Sometimes a pregnant woman with fibroids will need to stay in the hospital for a time because of pain, bleeding, or threatened preterm labor. Very rarely, myomectomy may be performed in a pregnant woman. Cesarean birth may be needed after myomectomy. Fibroids decrease in size after pregnancy in most cases.

A trial of labor is not recommended in patients at high risk of uterine rupture, including those with previous classical or T-shaped uterine incisions or extensive transfundal uterine surgery. Because myomectomy also can produce a transmural incision in the uterus, it often has been treated in an analogous way. There are no clinical trials that specifically address this issue; however, one study reports no uterine ruptures in 212 deliveries (83% vaginal) after myomectomy (74).

Pooled data from several case series of laparoscopic myomectomy involving more than 750 pregnancies identified one case of uterine rupture (39, 40, 75-77). Other case reports have described the occurrence of uterine rupture before and during labor (78-80), including rare case reports of uterine rupture remote from term after traditional abdominal myomectomy (81, 82). Most obstetricians allow women who underwent hysteroscopic myomectomy for type O or type I leiomyomas to go through labor and give birth vaginally; however, there are case reports of uterine rupture in women who experienced uterine perforation during hysteroscopy (83-85). It appears that the risk of uterine rupture in pregnancy after laparoscopic or hysteroscopic myomectomy is low. However, because of the serious nature of this complication, a high index of suspicion must be maintained when managing pregnancies after this procedure.